By Stephen Fisher, 5th July 2024

Yesterday was the tenth time since 1922 that voters in Britain kicked out a government after an economic crisis.

What was truly extraordinary is that since the 2019 election the Conservatives twice changed prime minister in an attempt to rescue themselves, each after an economic crisis, and then Rishi Sunak presided over a third economic crisis.

Governments tend to win elections, except after economic crises. That tendency now accounts for 20 of the last 28 elections. In a further three elections the government rescued themselves by changing prime minister after a crisis (dropping Lloyd George in 1922, dropping Eden after Suez, and dropping Thatcher after the 1990 recession). So, a combination of economic crises and political changes at the top can account for who governed after 23 of the last 28 elections, including all the elections since 1987.

Yesterday’s election result fits a theory of UK elections I developed in this paper and summarised in this bloglast year, in which an economic crisis is defined to be a recession or a devaluation from a fixed exchange rate. The table below shows how all 28 elections since 1922 fit that pattern, or not. The blog discusses how the exceptions are either near misses of exceptional short-parliaments.

Table: Economic crises, post-crisis political changes of PM and government electoral fortunes since 1922

| Post-Crisis Political Change of PM | Government won | Government lost | Total | |

| No economic crisis | No | 10(1935, 1955, 1966, Oct 1974, 1987, 2001, 2005, 2015, 2017, 2019) | 3(1923, 1924, 1951) | 13 |

| Economic crisis since the last election | No | 2(1950, 1983) | 10(1929, 1931, 1945, 1964, 1970, Feb 1974, 1979, 1997, 2010, 2024) | 12 |

| Yes | 3(1922, 1959, 1992) | 0 | 3 | |

| Total | 15 | 13 | 28 |

Even though there have been post-crisis political changes of PM since 2019, the 2024 election is not listed in the bottom row because there was a recession (in 2023) after Sunak took office.

Shortly after the 2019 general election the world was hit by the covid pandemic: a health crisis, but also an economic one. GDP is thought to have dropped by over 10% in 2020, the largest since the Great Frost of 1709 led to an estimated 13% drop.

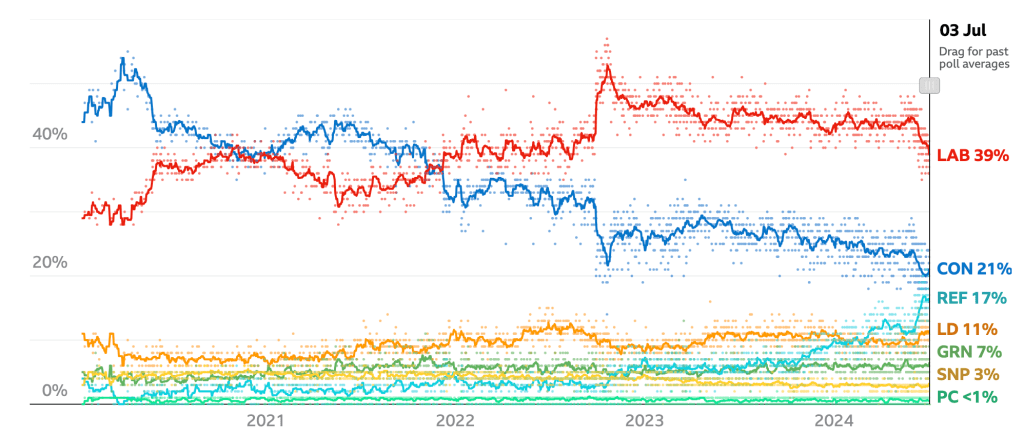

That did not immediately lead to loss of public support for the government. But the cost of lockdown to the public purse contributed to problems later on. Focus on tackling covid and the success of the vaccine rollout meant that in June 2021 the Conservatives had a 10-point lead over Labour in the polls. That was not much less than the 12-point lead they enjoyed at the 2019 general election.

Opinion polls from the 2019 to just before the 2024 general election

Source: BBC

As the world’s economy restarted after the pandemic, inflation and the cost-of living crisis rose rapidly in the late summer of 2021. That included a rise of gas prices, well before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and before the partygate revelations.

Support for the Conservatives dropped 7 points from their June 2021 peak to just before the partygate revelations on 30 November 2021 (the crossover point for Conservatives and Labour in the graph of polls above). But Conservative support dropped by only a further 4 points in the immediate aftermath of partygate. That suggests that more of the drop in Conservative support in the second half of 2021 was due to economic difficulties than to partygate.

Given that Boris Johnson managed to win a big majority despite being no paragon of virtue, it is not straightforwardly obvious that those who voted Conservative in 2019 should have turned against him over breeches of covid regulations. Perhaps the partygate revelations may not have mattered so much if people were not already suffering economically as we went into the winter of 2021. At the very least, we cannot assume that the effect of the partygate revelations was entirely separate from the declining economic circumstances.

As the cost-of-living crisis worsened in 2022, especially after the turmoil that followed the Ukraine invasion, Conservative poll ratings tumbled. In Westminster they talked of Boris Johnson being brought down by the three Ps: partygate, Paterson and Pincher. Few voters now remember details, if anything, of the last two. Bad local election results and Labour’s 6-point lead in polls in the summer of 2022 also contributed to Conservative MPs forcing out Boris Johnson.

Liz Truss as prime minister is remembered for provoking a market crisis over unfunded tax cuts. But a large part of the projected deficit was an estimated cost of over £100bn of the September 2022 energy price guarantee. There was big public support for that energy price cap plan, with most saying it did not go far enough. There are important questions here about how realistic the public were about the extent to which the British government could borrow money to pay gas bills without incurring adverse consequences of upsetting financial markets.

When Rishi Sunak took over markets stabilised, but economic stresses continued to damage public services and household disposable incomes. Last year saw another recession: a third economic crisis for the third prime minister since the last election.

Little wonder support for the Conservatives continued to decline in the polls.

If that analysis is even roughly right, the outcome of the election was mostly set before the campaign started. The Conservatives did not lose because of D-Day, betting allegations, or anything else in the campaign. The likely outcome was clear well before the election was called. The campaign was an opportunity to recover things, but it was always a longshot.

In the framework of my paper, the 2023 recession is indicative of an economic crisis after Rishi Sunak became PM. Had that been avoided, then maybe Sunak could have been a prime minister in the mould of Bonar Law, Harold Macmillan, and John Major. They all became prime minister in mid-term for political reasons after an economic crisis, and they all went on to win the subsequent election.

But even if Sunak had managed to avoid a recession, his premiership started with so many economic difficulties it is hard to see how he could have ameliorated the problems enough for the Conservatives to secure re-election.

The lesson for the incoming Labour government is obvious: try to avoid recessions.

Avoiding recessions is not just economically and socially desirable, but a paramount political priority for governments that want to stay in power.

Less obvious, and not enough discussed, is the extent to which the Conservative government was brought down by energy prices, and how many of the economic crises that afflicted previous governments were initially caused by – or subsequently exacerbated by – energy crises.

Coal prices led to the 1926 general strike that brought down Stanley Baldwin at the 1929 election. Coal miner strikes and the 1973 oil crisis brought down Heath in 1974. The oil price spike following the Iranian revolution contributed to the depth of the early 1980s recession which would have done for Margaret Thatcher, had it not been for the Falklands crisis.

Labour had a poll lead from January 1993 until September 2000, but then lost it during a petrol crisis. Tony Blair managed to resolve the problem quickly, and Labour rapidly recovered in the polls. But the episode shows that government support depends on making sure fuel and energy supplies continue at acceptable prices. Finally, the 2007-8 oil price spike exacerbated the 2008-9 Great Recession that did for the Brown government.

The energy price rises that contributed hugely to the 2021-24 cost of living crisis now join the list of energy crises that contributed to the demise of at least four governments, and trouble for others.

Labour is hoping that their plans for green energy will bring benefits in cost and security, and so help reduce the chances of an economic crisis.

While energy and economic crises were, I believe, the crucial factor explaining why the Conservatives lost power this week, they do not explain everything about this election.

Not least the theory of government survival based on economic crises says nothing about why the vote against the Conservatives were split so evenly across so many parties.