By Stephen Fisher, 2nd May 2025.

Updated with all of Thursday’s election results in. That is 23 councils, 1639 seats across 1399 wards/county electoral divisions, 6 directly-elected mayoralties, and 1 parliamentary by-election.

Verdict:

Extraordinary for Reform, good for the Liberal Democrats, mixed for Greens, bad for Labour, and extremely bad for the Conservatives.

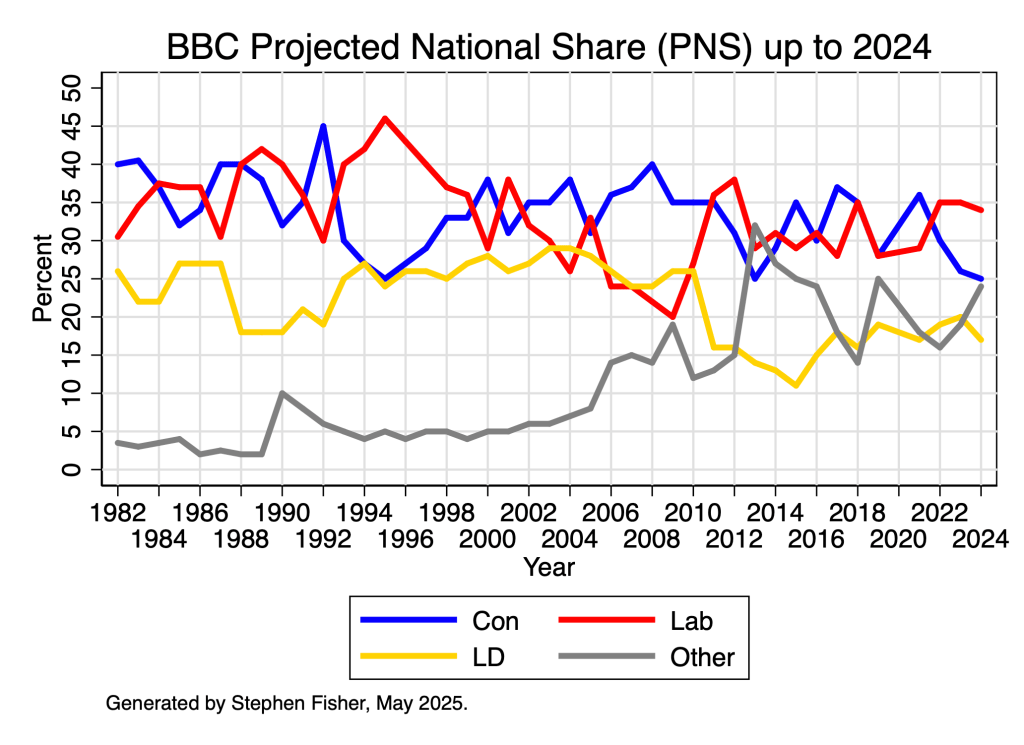

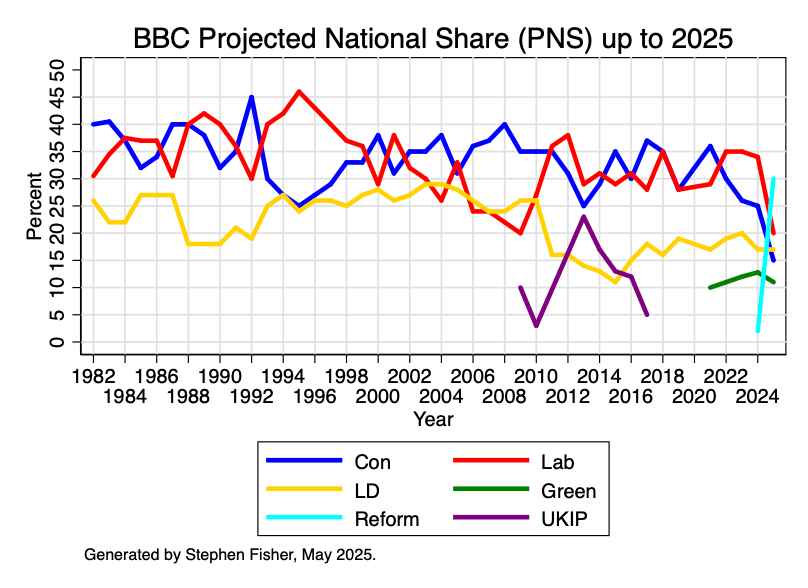

The graph below gives you a sense of how dramatically things changed this year. For an explainer of the PNS see here.

Reform UK:

- Top of the poll, with 30% in the BBC Projected National Share (PNS) of the vote, up from just 2% in last year’s local elections (due to not fielding many candidates in 2023). Reform comfortably beat UKIP’s best result of 23% in 2013.

- Won control of +10 councils, despite starting with no seats at all: Derbyshire, Doncaster, Durham, Kent, Lancashire, Lincolnshire, North Northamptonshire, West Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, and Staffordshire.

- Largest party on a further 4 councils that are “No Overall Control”, so 14 out of 23 in total: Cornwall, Leicestershire, Warwickshire, and Worcestershire.

- Won the popular vote in 14 authorities.

- Won the Runcorn and Helsby parliamentary by-election, albeit by just 6 votes, with a 17-point swing. Overturning a majority 34 points or more has only happened in 17 previous by-elections.

- Won 677 council seats: 41% of the total.

- Won the Greater Lincolnshire and Hull & East Yorkshire mayoralties, and came a close second in Doncaster, North Tyneside and the West of England