By Stephen Fisher, 7th February 2025

The government is only seven months old. Nonetheless, opinion polls show that Labour support has dropped by massive 9 points from the modest 35 per cent of the GB vote they achieved at last year’s general election. Now Labour, Reform, and the Conservatives are roughly level pegging in the mid-20’s.

Some commentators have suggested we should not take opinion polling seriously so early in the election cycle. Afterall the next election does not need to be before August 2029. Plenty of time for things to change?

No. The combination of dire economic indicators, forecasts, and opinion polls, in light of British electoral history, suggests Labour are (perhaps unfairly) already at high risk of losing their majority at the next election. Once down heavily due to an economic crisis, governments rarely win elections; still less prime ministers.

Here are some reasons why Labour, and particularly Keir Starmer, should be seriously concerned.

No government has suffered even close to a 9-point drop from their general election share within their first year and gone on to win re-election. Thatcher’s government dropped by 10 points within a year and a half of the 1979 election because of the 1980-1 recession. She was on course to lose the next election; only winning because of the Falklands war.

The 9-point drop in the Labour vote is big. If replicated in a general election, according to classic uniform change projections (and recent MRP models provide similar estimates), Labour’s 174-majority would be wiped out. With just 291 seats, Labour would be 35 seats short of a majority. While that would be enough to govern with the Liberal Democrats (on 72 projected seats) it would be quite a come down.

While uniform change projections are likely to be a reasonable guide, things could be much worse for Labour. If their vote share drops more heavily in the seats they are defending (as the Conservatives’ did in 1997 and 2024 and Labour’s did in Scotland in 2015) then losses would be even greater.

Tactical voting between the Conservatives and Reform party supporters would reduce the Labour seat tally further still. An electoral pact between them would be devastating for Labour, but hardly a surprise.

The decline in Labour vote intention is underpinned by a decline in government approval (from a modest 28% to just 16% according to YouGov), and a massive rise in disapproval (from 32% to 64%). Evaluations of Keir Starmer’s performance as prime minister have also worsened.

Bad polling figures for Labour appear to be largely due to concerns about the economy. The number of people saying the economy is one of the most important issues facing the country has been high since the start of the cost-of-living crisis in 2021. That measure of economic concern dropped with the arrival of the Labour government but has been rising over recent weeks. Last month Ipsos found that as many as 80% of people are “closely following” stories about the rising cost of living, much more than any other news they asked about, suggesting public anxiety about inflation.

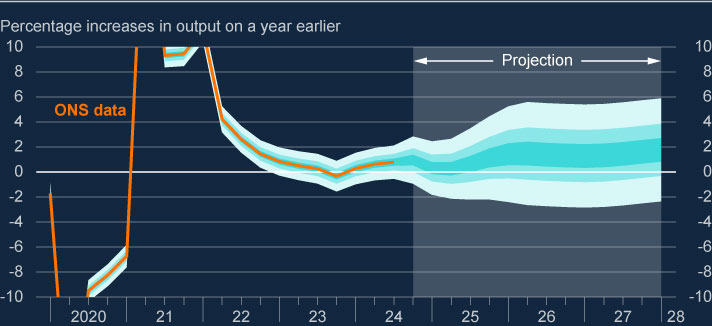

Economic anxiety is unsurprising given the poor performance of the UK economy. Yesterday the Bank of England announced that “UK GDP growth is estimated to have been zero in 2024 Q3, [and] projected to have fallen by 0.1% in Q4,” and to rise by 0.1% in 2025 Q1. Given the uncertainty in those estimates and projections (as evident in the Bank’s chart for annualised growth below) there is a high probability (close to 50%) that the UK has been in a recession since October. That is to say, there is a fair chance final figures will show GDP drops in both the final quarter of 2024 and the first quarter of 2025. Even if we are not in a recession now, the uncertainty in forecasts for future GDP figures mean a high risk of a recession before the next election.

Source: Bank of England, 6th February 2025

While near zero positive growth and near zero negative growth are not very different from each other, and both are bad, the history of UK elections shows that technical recessions are highly correlated with subsequent election outcomes. Along with devaluations from fixed-exchange-rate systems they are indicative of economic crises.

Governments tend to win elections, except after economic crises, unless they change prime minister after the crisis. That pattern accounts for 23 of the 28 elections since 1922, including all the elections since 1987. Of the ten economic crises that brought down governments, eight involved recessions. Apart from three silly elections that should not have happened (1923, 1924, and 1951), all of the governments that avoided a recession or devaluation since 1922 have been re-elected. That was true even with very little growth, such as for the 2010-15 government. So, there is strong evidence that governments need to avoid recessions to survive and their prospects are good if recessions are avoided.

The idea that there is plenty of time for the government to recover from an early recession is false comfort for Labour. With the debatable exception of 1945, the economic crises that have apparently led to electoral defeat either happened, or had their origins, within the first two years of a prime minister’s term. (Details of the cases supporting that claim are below.) Perhaps the shortest period from winning an election to an election-losing economic crisis was the five months from the April 1992 election to the September 1992 ERM crisis, which set John Major on course to lose the 1997 election. There is no sign in the UK historical record that early recessions do not matter for subsequent election outcomes. Instead of recovery from early setbacks, economic crises break government reputations. Like all reputations, once broken they are hard to fix.

The few cases of governments winning elections after economic crises do not make happy reading for Sir Keir Starmer.

No prime minister has won re-election after removing their chancellor mid-term. Sacking Norman Lamont did not save John Major. No other PM (since at least WW1) has removed a chancellor mid-term and survived to fight a general election. There have been several prime ministers that have sacked chancellors in an attempt to resolve a crisis only to be undone themselves. On that basis, it is unclear whether sacking Rachel Reeves would help Labour win the next election without also undermining Starmer’s own position.

By contrast, on four occasions majority parties have rescued themselves by changing prime minister after a crisis: dropping Lloyd George in 1922; Macdonald in 1935; Eden after the Suez crisis; and Thatcher during the 1990 recession. The only prime ministers in the last 100 years to have won re-election after an economic crisis were Clement Atlee and Margaret Thatcher. Atlee may have survived the 1950 election but his majority collapsed from 147 to 6, and it was not long before he lost the 1951 election. Thatcher, as mentioned above, was only saved by the Falklands War. These cases suggest it is hard for prime ministers to restore their party’s popularity after a crisis, but new prime ministers sometimes can.

If the Labour party does start to think about changing prime minister, there may be a danger of going too early, especially if there is a risk of an economic crisis between a leadership change and the next election. Gordon Brown lost in 2010 due to the financial crisis that started shortly after he became prime minister in 2007. While Rishi Sunak may never have been able to rescue the Conservatives, it did not help that he presided over the 2023 recession. By contrast, Stanley Baldwin was remarkably adept in facilitating switches of prime minister only very shortly before the 1922 and 1935 elections; both times securing re-election for the Conservatives despite economic crises under their watch.

It is too soon to say that Labour are definitely on course to lose their majority at the next election. But things are not looking good for them. The Bank of England yesterday predicted a rise of inflation, halved their growth forecast for this year, and projected little growth and (although they did not use these words) a substantial risk of recession for much of the rest of the parliament (see chart above). Add to that the geopolitical turmoil.

Also, the public do not believe the government will turn things around before the next election. Labour’s manifesto was titled Change. But last month, Deltapoll (for the Institute of Government) found that only 28% think the government would be effective at improving the lives of people like themselves within four years. Some 62% said the government would be ineffective.

None of this analysis implies that this government deserves to lose an election because economic outcomes. Many previous governments seem to have been voted out because of circumstances beyond their control. As in the 1920s, early 1930s and 1970s we may now be in a period where UK governments of any colour and complexion struggle to win re-election.

How government election losses have mainly been due to economic crises early in the election cycle

Conservative loss at the 1929 election: This was a result of the May 1926 General Strike and accompanying recession that took place less than two years after the October 1924 election.

Labour loss at the 1931 election: Having won the May 1929 election, the Labour government collapsed in disarray in August 1931 after failing to agree on how to respond to the economic shock waves from the Wall Street Crash and the start of the Great Depression.

Conservative loss at the 1964 election: The seeds of Harold Wilson’s victory were sown with the 1961 recession (less than 2 years after the October 1959 election). The Conservative government fell further behind in 1962 and 1963 as inflation and unemployment worsened (Butler and Stokes, 1971, Chapter 14). The partial recovery in 1964 was insufficient to save the government.

Labour loss at the 1970 election: As Kenneth Morgan wrote in The People’s Peace, “the Labour government’s standing rapidly went into decline after the successful outcome of the March 1966 general election. Two particular episodes mark the boundaries of this descent into the grave. Its start came in the third week of July 1966, when Harold Wilson’s ministry was cast into disarray by a huge assault on sterling and on the gold and dollar reserves. The nation, Wilson warned darkly, had been ‘blown off course’ by an unspecified nexus of conspirators.” After a series of short-term crisis management policies, the government famously devalued the pound by 14.3% in November 1967. Labour lost their lead in the polls at that point and went on to lose in 1970.

Conservative loss at the February 1974 election: This arguably had its origins in economic difficulties that the government inherited, and then they worsened throughout Heath’s term. Even though the crisis only reached its peak in 1973 (with a recession, the miners’ strike, and the three-day week), the Conservatives were well behind in the polls within a year of coming to office.

Labour loss at the 1979 election: After the October 1974 election the Labour government suffered a recession mid 1975. They lost their lead in the polls during that recession and never regained it for more than a few weeks at a time.

Conservative loss at the 1997 election: This had its origins in the ERM crisis of 16th September 1992, just five months after John Major won the 9th April 1992 election.

Labour loss at the 2010 election: This was due to the financial crisis that started in late 2007. That was not close to the 2005 general election but unfortunately for Gordon Brown it was soon after he became prime minister.

Conservative loss at the 2024 election: Conservative support in the polls stayed high during the Covid recession but declined from the start of the cost-of-living crisis in 2021. It is not clear whether Rishi Sunak could ever have secured re-election given the dire economic and fiscal circumstances he inherited from Liz Truss in 2022, but a further recession early in his term in 2023 may have contributed to the Conservatives’ eventual election loss.

For further details, see my working paper at https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/beh78_v1, (currently under revision).