By Stephen Fisher, 30th April 2025.

In recent years, changes in vote-intention opinion polls have generally provided a reasonable guide to headline gains and losses at local elections. Most of the seats up this year were last fought in 2021. Table 1 shows how party support in the opinion polls has changed since then. Reform UK are ahead, just, and never before in England has vote intention been so evenly divided between five parties.

Table 1. Opinion poll changes from 2021 locals to 2025 locals (GB)

| % | 2021 polls | 2025 polls | Change |

| Con | 41 | 23 | -18 |

| Lab | 36 | 24 | -12 |

| LD | 7 | 13 | +6 |

| Reform | 2 | 25 | +23 |

| Green | 5 | 9 | +4 |

How might these changes translate into net changes in local council seats?

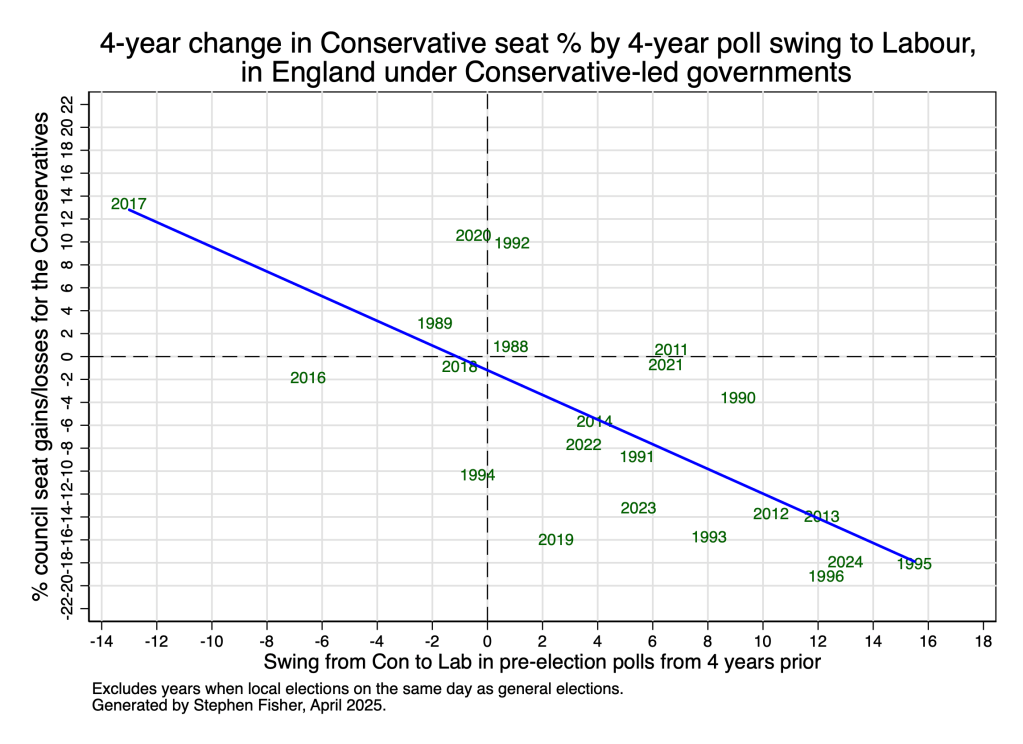

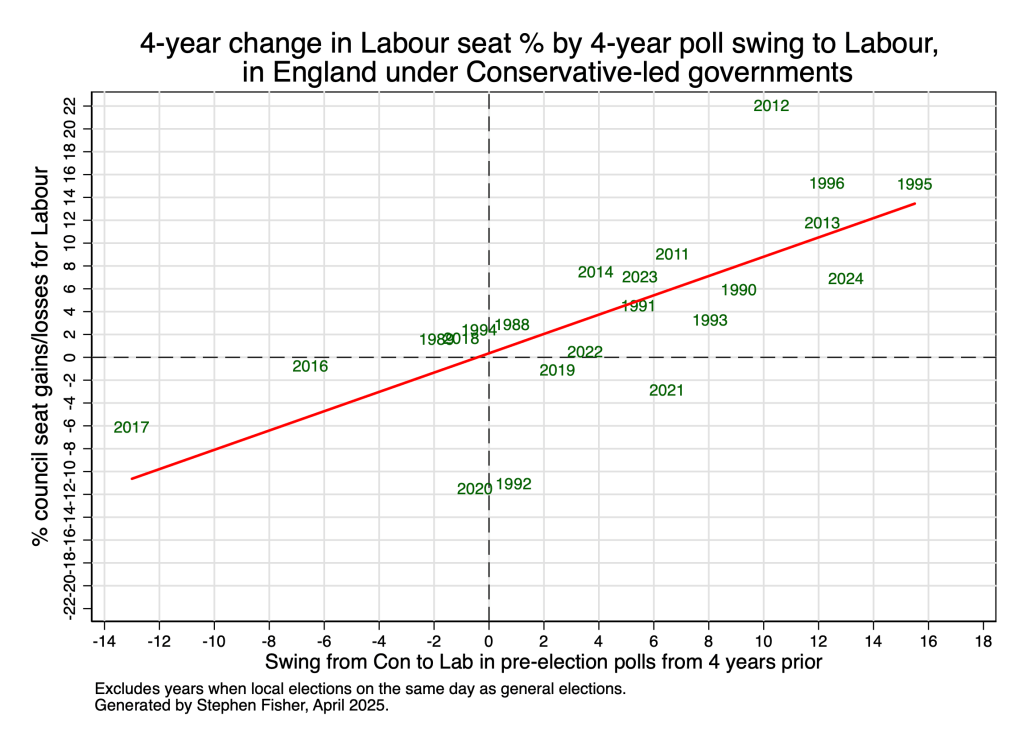

The first two graphs below show how — under Conservative governments — the shares of seats up gained or lost by the Conservatives and Labour were relatively closely related to the Conservative-Labour swing in the polls. Swings to Labour were followed by council seat gains for Labour and losses for the Conservatives. Last year was no exception.

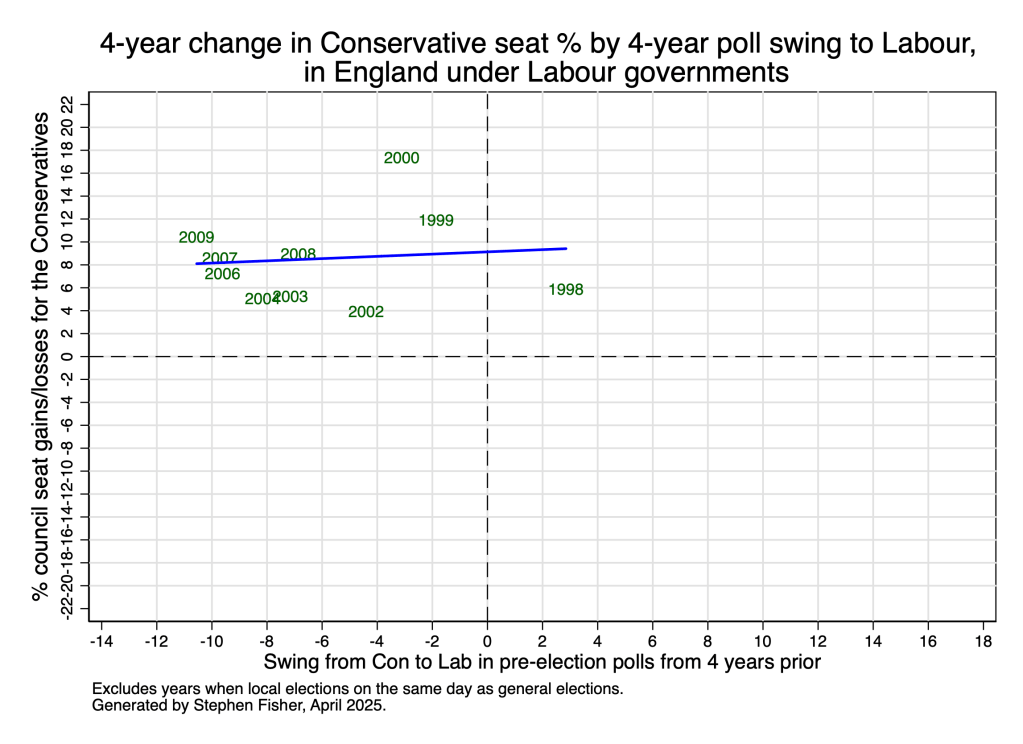

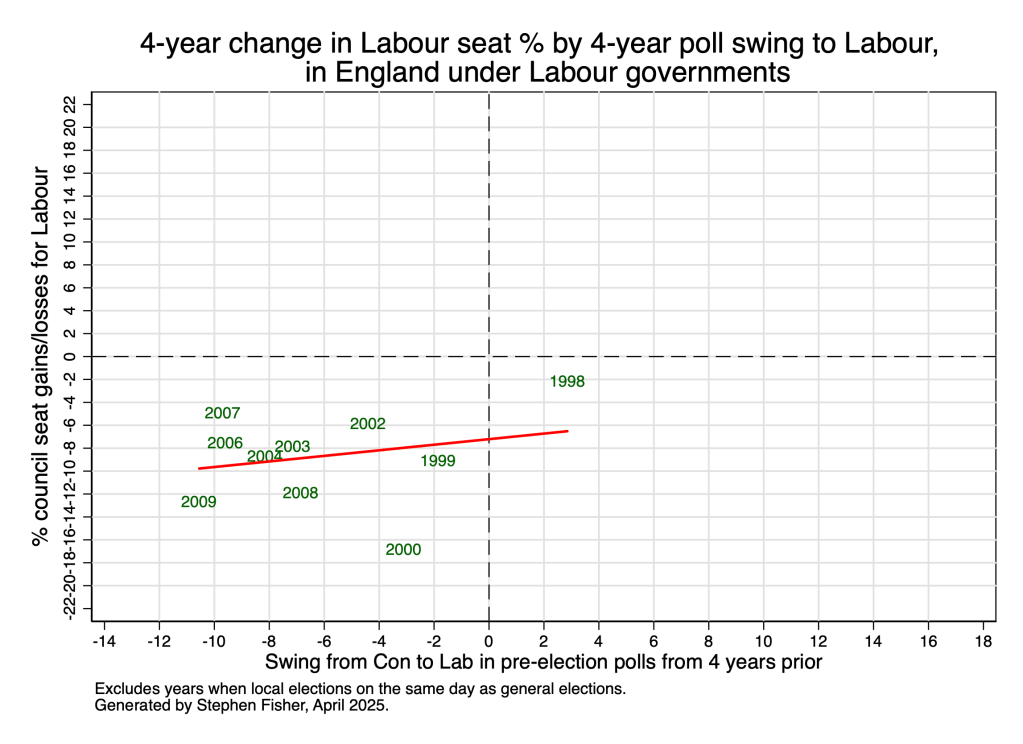

Now we have a Labour government, things may be different. During the Blair-Brown years Labour consistently suffered net losses and the Conservatives consistently made net gains, almost regardless of the swing in the polls between those two parties. (The regression lines in the two graphs below are essentially flat.) Moreover, in the first set of local elections after Labour came to power, the Conservatives made gains and Labour suffered net losses despite a swing to Labour in the polls between 1994 and 1998. On the basis of the pattern of local elections under New Labour, we might expect net gains and losses in the order of 8 per cent of the seats up every year. If that happens this week then it will roughly Labour -130 and Conservative +130.

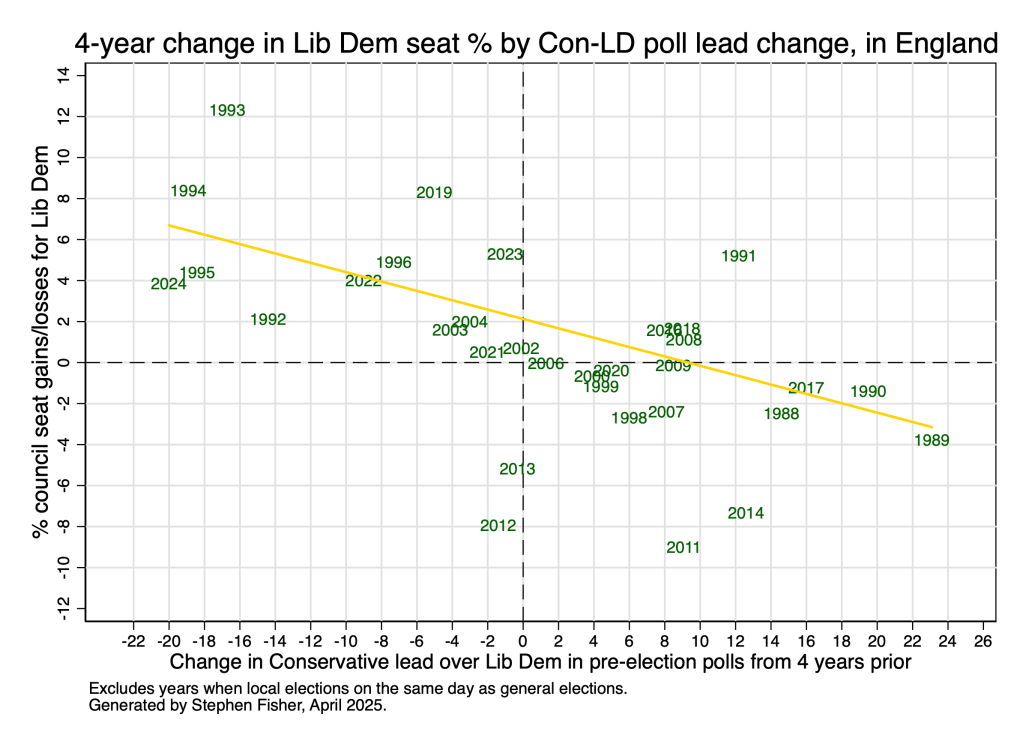

Liberal Democrat local seat tallies in England have historically been linked primarily to the swing between them and the Conservatives. In the graph below the regression line is fitted excluding the coalition years (2011 to 2014), when the Lib Dems suffered even heavier losses than the Lib Dem to Conservative poll swings would normally imply.

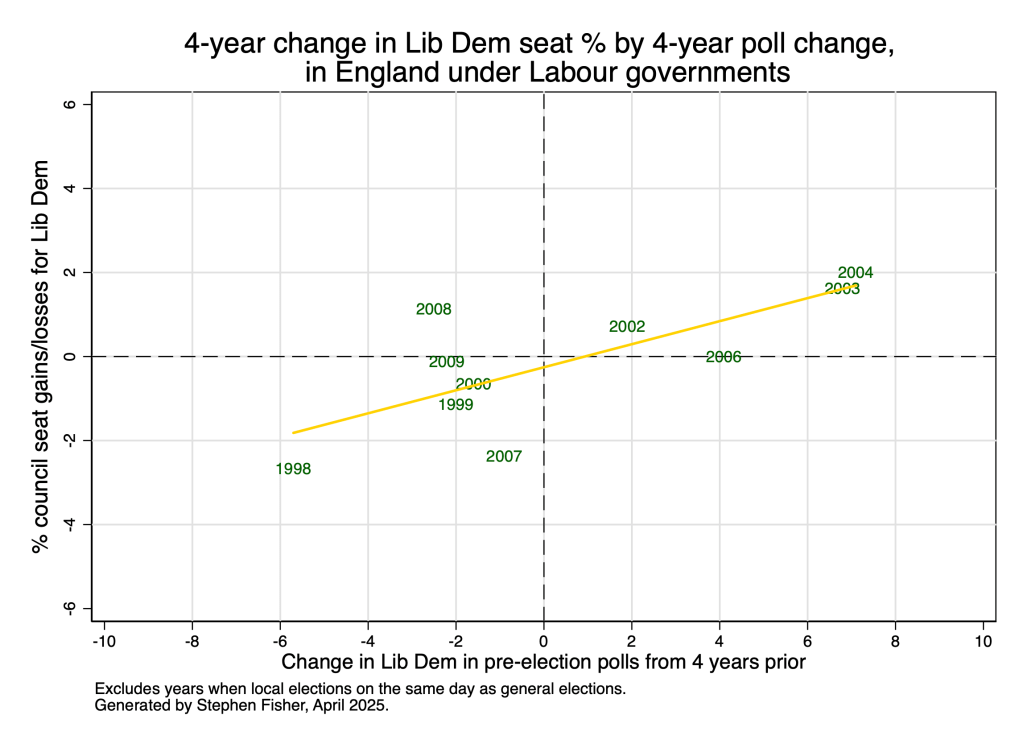

During the Labour government years, Liberal Democrat gains and losses were modest, but they were positively correlated with the party’s performance in the polls.

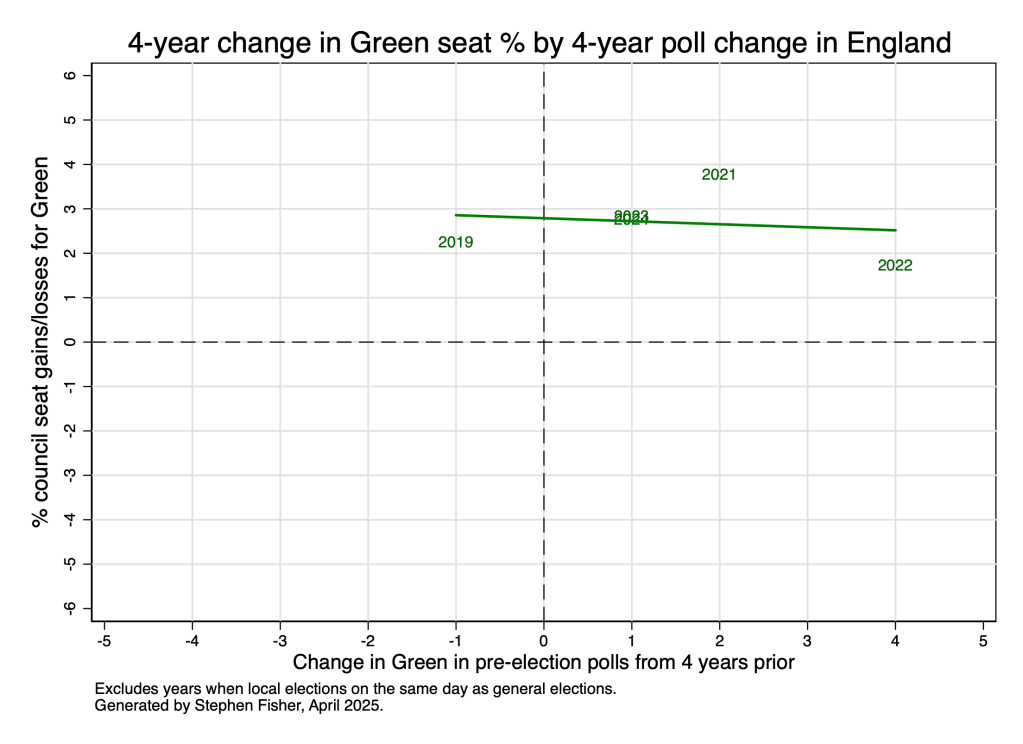

In recent years the Greens have been making steady gains at local elections. But intriguingly the scale of the net gains (as a proportion of the seats up for election) has not varied much with their performance in the polls.

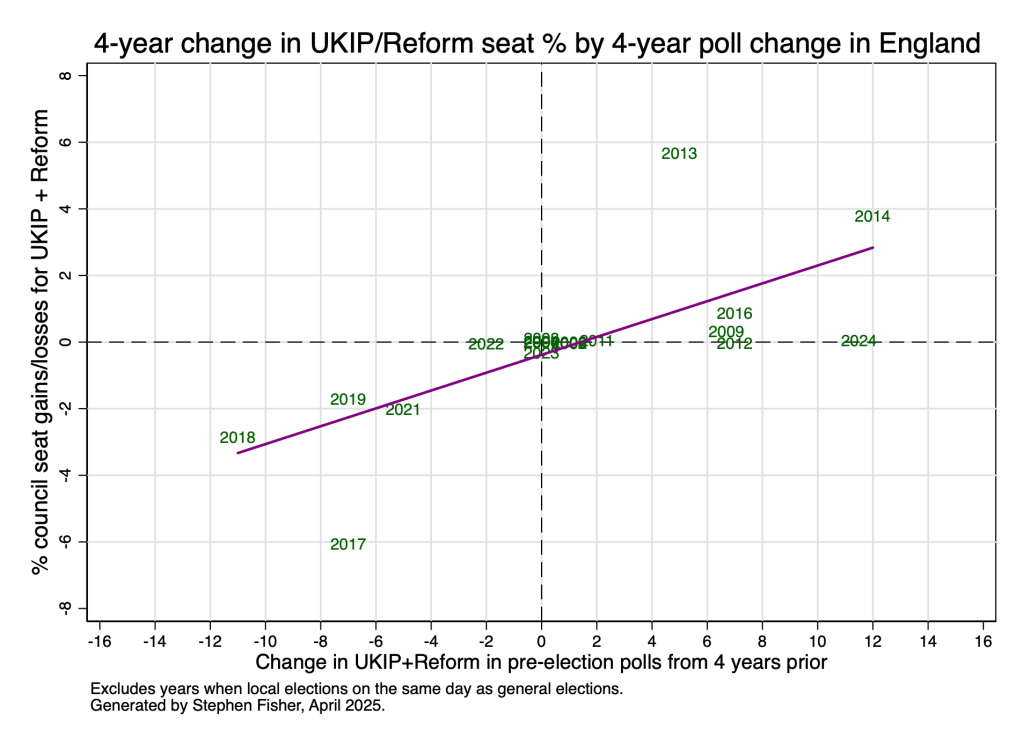

Reform UK won just 2 seats in each of the last three rounds of local elections. Their predecessor, the Brexit Party, did not contest the 2019 local elections. Before that, UKIP were the largest populist right party. Under Nigel Farage they made net gains of +139 and +163 in 2013 and 2014 respectively. At the time these developments were big news, but as the graph below shows — as a proportion of the seats up — only the 2013 performance was comparable to their rise in the opinion polls. In 2014 UKIP were up 14 points in the polls but made net gains of seats amounting to less than 4 per cent of the seats up. Even more strikingly, last year Reform were up nearly 12 points in the polls, but they only won 2 seats out of 2659: less than 0.08%. At that rate they will again win just 2 seats this year despite being first in the opinion polls.

But there are good reasons to think Reform UK will do a better job of translating votes to local council seats this week. There was one year when the size of UKIP’s local election seat tally reflected their rise in the polls, which is a particularly relevant point of comparison this year. Both 2013 and this year are English county council election years. In 2013 UKIP contested 72.8% of the seats, much more than the party typically managed. Last year Reform only contested 11.5% of seats. This year Reform are contesting virtually all the seats, with more candidates than any other party. That greater number of candidates, together with their support in the polls reaching a critical level, might mean Reform translate their level of support in the polls into a similar, or greater, share of seats.

Local Seat Forecasts

My local election forecasts are based on regression models of seat share change on opinion poll share. In recent years I have used Conservative to Labour swing in the polls to forecast seats for those parties. This year, given the rise of Reform, that approach would implausibly suggest a modest set of gains for Labour and losses for the Conservatives. Instead of swing, for Table 2 the regression model for the Conservatives uses just the Conservative poll change, and likewise for Labour. Both parties are down heavily in the polls since 2021, so both are projected to make substantial net losses. (Given that experience of the Blair/Brown years discussed above may not be repeated, the regressions are run using all local elections since 1985 that were not on the same day as a general election.)

Table 2. Model-based forecasts for net seat gains/losses at 2025 local elections

| Forecast | |

| Con | -350 |

| Lab | -140 |

| LD | +75 |

| Green | +65 |

| Reform | +375 |

| Others | -25 |

The Liberal Democrat model is unchanged from last year. It is based on Con-LD swing, with allowance for additional losses during the coalition years.

For the Greens and Reform, the forecasts are simply what those parties should get if they get an additional 1% of the seats up for every extra percentage point increase in their poll rating since 2021. For the Greens, that method produces a forecast very similar to the 50+ net gains a regression model suggests. For Reform, regression models only project +100 gains, because they extrapolate the generally poor record of UKIP and Reform in translating popularity in the polls to seats in councils. Instead, the +375 forecast Reform gains provides a reasonable benchmark of what Reform should achieve to match their showing in the opinion polls.

The figure for Others in Table 2 is just an accounting balance. All five party forecasts are estimated separately.

The models do not take into account the number of seats each party is defending. Since English shires are traditionally Conservative territory, and 2021 was an especially good set of local election results for the Conservatives, Labour are defending just 285 seats this week. So, the model unwittingly projects Labour to lose nearly half their seats. That seems unlikely. Meanwhile, I suspect that with 995 seats to defend, the Conservatives will lose more than 350.

Post-mortem for 2024 forecasts

Table 3 shows the forecasts from last year and the actual outcomes. Lord Hayward deserves congratulations again.

Table 3. Forecasts and actual local election net seat gains/losses for 2024

| ElectionsEtc | Hayward | Actual | |

| Con | -390 | -400 or more | -473 |

| Lab | +320 | +200 to +250 | +186 |

| LD | +100 | +100 | +104 |

| Others (inc Green) | -30 | +183 | |

| Green | +30 | +74 | |

| Reform | +2 |

As I published my forecasts last year, I said, “they do not take direct account of the rise in the Reform party share, nor perhaps more importantly given their success last year [2023], the big rise in the number of Green party candidates relative to the number of seats up for election. Based on last year’s experience, I would expect the Conservatives to do worse than the model suggests, and the Liberal Democrats and Others (mainly Greens) to do better.”

I was wrong to expect Liberal Democrat overperformance. They have tended to overperform my model since the coalition government ended in 2015, and they did so massively in 2023. But last year the model was basically spot on for them.

Overall, I would say that the models did well, especially given how minimalist they are. However, they substantially overestimated Labour and underestimated the Conservatives. Models for those parties are based on the swing in the polls. So the local seats forecast error may have been related to the polling error at the 2024 general election (just two months after the locals) when the average of the polls overestimated Labour by 3.9 points and underestimated the Conservatives by 3.0 points. I would not go so far as to claim that the direction of the local seats forecast error should have been taken at the time as a sign that the polls were likely to overestimate the Labour lead over the Conservatives.

Before the 2024 local elections, Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher said that, “if the Conservatives repeat their poor performance of 2023, when the NEV put them below 30%, they stand to lose up to 500 seats – half their councillors facing election. Labour may make about 300 gains, with the Liberal Democrats and Greens both likely to advance.” The Conservatives actually got 27% in the NEV, and suffered fewer than 500 losses. Labour did not achieve the 300 gains Rallings and Thrasher thought they may be able to achieve.

Many thanks to Colin Rallings, Michael Thrasher, David Cowling, Rob Ford and the BBC for help compiling the data over the years.